" I haven't been

everywhere, but it's on my list." - Susan Sontag

January 16 - 20 Recife/Olinda

You would

think that with having booked a guaranteed reservation and paying $20 for it

that we would have gotten a room at the hotel we selected. Well, that was not the case. They had overbooked and had made a

reservation for us in a nearby, lower quality, hotel. In addition, we wound up spending another 1/2

day waiting to get moved out of the substitute back into the hotel we'd

originally booked in the first place. We

were not happy and promptly asked for a discount and asked to get our booking

service fee refunded. Fortunately the

booking agent did refund the $20, no questions asked which we did appreciate.

Brazilian run

hotels often leave a lot to be desired.

Things just don't work right.

Walls will have peeling paint, toilet seats will be broken, beds lumpy

and saggy, showers lukewarm. The lobbies

may look upscale and nice. But just wait

until you get into the room. Even though

these types of conditions often are found in Latin America

hotels, in other countries the prices are quite reasonable. You feel as though you are getting what you

pay for. Stay in the $15 to $20 range

and that's what you get, pretty low quality room. Get up to around $30 to $40 and you get

something fairly nice.

However, not

so in Brazil,

along the beach, in high summer season.

Here we were paying around $70 per night for an old room with lumpy bed

and only half was very poorly air-conditioned.

The lobby was very nice, complete with doormen, concierge, and uniformed

desk clerks. The pool was one of the

largest, cleanest pools we'd seen. But

the standard rooms were basically crummy.

Yet this is not uncommon throughout Brazil. In fact, the two very best hotels we stayed

in was the Ibis, part of the foreign owned Accor chain, and a small French run

pousada up in Belem. Sometimes it just

seems Brazilian hotels are way over valuing themselves or they just don't know

how to do things up to US or European standards.

Once we went

through the process of getting ourselves resituated into the hotel we'd

originally booked it was time to start seeing the town. Our first destination was the Museu do Homens

do Nordeste. The museum is supposed to

house crafts and artifacts from the native people of the north east region. However, this we cannot confirm. We never got inside.

In the

afternoon, we got on one bus heading downtown to the location where our

guidebook said we needed to get a second bus to the museum. This second bus had the name "dois

Irmaos" (two brothers). It turns

out there are a lot of buses with this name and naturally we weren't on the

correct one. So we soon found ourselves

headed right back through town to where we'd begun this trek and a little

beyond. The helpful bus driver then directed us where to get off and which bus,

the third, to get on to get to the museum.

This entire running around took over an hour.

With all this

running around we were so chagrinned to find that the Museu do Homens do

Nordeste was closed for renovation. The

only thing open was this art gallery housing a strange hairdryer contraption

that some modern artist claimed could read his thoughts. It didn't work and practically started a

fire. The only thing we got out of it

was finding a lady who spoke English well enough to give us directions for the

buses back to our hotel (two more buses at that).

So after

spending about $7 on buses and several hours to get to a museum that was closed

the only thing we could say we accomplished for this day was to have a round

about tour of the suburbs of Recife.

Day 2 was a

whole lot better. We managed to find the

direct bus to Olinda,

which was on a street different from the one indicated in the guidebook. We managed to see all the churches in town

and wander the streets before early afternoon.

Another direct bus took us back to within 2 blocks of the hotel, we now

knew the street numbering system so we could be more accurate as to where to

get off. And we even managed to get in a

good long swim in that nice pool we were paying an exorbitant fee to have. That's the way it is with independent

travel. Some days turn out a complete

disaster. Fortunately most do not.

Olinda is another colonial town located around

15 km or so north of Recife. Throughout Portuguese and Brazilian history

these two cities have been linked financially and politically. Olinda has

always been the center of the rich sugar plantation owners while

Recife with its rivers

and reefs has been the port. In the 17th

century revenues from the sugarcane industry made the Recife/Olinda combination

one of the most prosperous cities in Brazil,

second only to Salvador. This prosperity made this region a very

attractive prize for other European powers as well, the Dutch in particular.

While other

areas of Brazil

were able to resist incursions from other envious European interests, the

Recife/Olinda area was not. The Dutch

first managed to grab Recife

in 1624 under the flag of the Dutch West India Company. This first invasion was repelled a year later

when a combined Spanish/Portuguese army of 12,000 tossed them out. The Dutch returned in 1629 and this time

managed to hold the city as well as large holdings in the northeast until

1654. The sugar plantation owners

resented having the non-Catholic Dutch in charge and managed to put together an

army to expel the foreign interests once and for all. It is rather interesting to note that during

the time the rather religious tolerant Dutch resided in Recife, the Jewish also came.

After the

Dutch left tempers between the plantation owners of Olinda

and the merchants of Recife

flared. This came to a head in 1710 when

the whole feud erupted into bloody warfare.

The merchants, with the economic power of the Portuguese Crown, gained

significant power while Olinda

declined. Eventually as the sugar

economy declined, Sao Paulo and Rio eclipsed the economic power of Recife/Olinda.

Today

Recife remains a busy

city and port although it still does not enjoy the economic and political clout

of its colonial days.

Olinda

has essentially become a quiet suburb of Recife. Because it hasn't had the economic power or

growing population of Recife,

it has been able to retain its colonial charm.

Recife,

on the other hand, has continued to grow, adding modern high-rises and

neighborhoods sprawling for miles around.

Olinda has the usual collection of one and two

story white colonial buildings with painted window and doorframes. There are a few craft shops, a few

restaurants, and the normal plethora of churches. The best was the Convento do Sao

Fransisco. The outside of the church was

rather plain. But inside are some of the

most beautiful blue and white tile frescos covering the walls. The tiles are all in Portuguese and usually

represent scenes from the bible. But

there are some scenes of every day life, which are far more interesting since

they give a glimpse into rural life in Portugal of that era. The ladies and men of wealthier classes

wearing the funny looking curly wigs in vogue at that time are most

interesting.

The way the tiles were placed on the

walls is most unique. The original block

or adobe wall is first stuccoed over flat and smooth. Then along the bottom 4 to 6 feet an extra

layer of stucco about 1 1/2 inches thick is applied. The upper edge of this layer is not a

straight line. Rather it undulates to

match the form the tiles will eventually take.

The blue and white tiles with their elaborate scenes are then applied to

this thicker layer. The whole thing

makes the tiles stand out almost as if there were just a thick painted board

attached to the wall. It's a most

unusual tile attachment method.

The way the tiles were placed on the

walls is most unique. The original block

or adobe wall is first stuccoed over flat and smooth. Then along the bottom 4 to 6 feet an extra

layer of stucco about 1 1/2 inches thick is applied. The upper edge of this layer is not a

straight line. Rather it undulates to

match the form the tiles will eventually take.

The blue and white tiles with their elaborate scenes are then applied to

this thicker layer. The whole thing

makes the tiles stand out almost as if there were just a thick painted board

attached to the wall. It's a most

unusual tile attachment method.

Over the

years some of the tiles have fallen off.

Rather than go through the trouble of putting the puzzle back together

correctly, they have placed tiles found on the floor in miscellaneous places

just to have the shape and blue and white color. It looks like a child attempted to put a

puzzle together and got it all wrong. It

would seem better just to leave the tiles off or to make a better effort to put

it back together right. As it is, these

spots look strange.

Recife was the subject of our final day before

beginning our air pass flights. Much of

old Recife has

been replaced over the years by modern buildings. Modern, of course, doesn't necessarily mean

20th century. Like most cities it has an

eclectic mix of 17th through 20th century structures usually assembled in a not

too pleasing manner. There are a few

gems. The theater, governor's palace,

and house of justice to name a few.

In the oldest

section of Recife

is one site that is probably the most important from a historical

perspective. During the 1630s when

Recife was under the

control of the Dutch, this area adopted the Dutch liberal religious views. Jews who had found a religious haven in the Netherlands contracted with the Dutch West

Indies company and migrated to Recife. They came with only the clothes on their

backs but soon grew to be a very prosperous and wealthy sector of society. Unfortunately for the Jews, when the

Portuguese regained control of Recife

they were unmercifully persecuted. Some

fled back to the Netherlands. But, some 23 found their way to New

Amsterdam, today's New York. So how many of the Jews in

New

York know that they came from the Netherlands

by way of Brazil?

The Jews brought

one innovation to Brazil

that today has been taken to an extreme that we've never seen elsewhere,

installment payments. In Brazil you can

buy virtually anything on installment.

Every single store lists prices either "a vista", payment in

full at visit, or in payments usually listed as 5XR$10, 3XR$50, 12XR$15,

etc. Meaning you make 5, 3 or 12 equal payments of so many

Reias. We're not entirely sure how it

works, but we think it may be done the way things were done in the US back in the

40s and 50s. You set up an account with

a particular store and then make payments on your account that match what the

particular purchase.

We just

couldn't believe the things you could put on this type of credit. Shoes, shirts, household goods, vacations,

medicines, everything. Of course, today

in the U.S.

we consolidate all those installment purchases into a single credit card, VISA,

Master Card, or whatever. That way

you're just making one payment for everything.

Not in Brazil. Just imagine the nightmare of keeping track

of 6 or 7 different purchases at a single store with different payment

schedules. I'll bet payments are missed

all the time.

Anyway, this

whole concept of installment payments did not exist in Colonial Brazil until

the Jews showed up. Obviously it's

become a favorite way to buy things today.

Good or bad, we think we'll stick to cash.

In the middle

of the oldest section of Recife

sits a building that looks like nothing more than one of the neighboring

houses. Inside you'll find one of the

better museums in Brazil,

from an English speaker's point of view that is. This was the location of the western

hemisphere's first Jewish synagogue. Its

precise location was discovered only recently.

Recent

investigations into documents made during the Dutch occupation of

Recife revealed that

there was, in fact, a synagogue. Enough

information was found that through triangulation they were able to find the

exact location where they thought it would have been. Excavations eventually located the sacred

pool of water that would have been on the ground floor. In addition several items of metal and glass

showing the star of David and the Minora were found thus confirming the site.

Today the

museum has a very good explanation of the history of the Jews in Brazil and a

recreation of how they think the synagogue might have appeared. With the exception of a few archeological

traces, everything you see is a recreation.

But, it's interesting none the less.

Elsewhere in Recife is a fort that was also built during

Dutch occupation. This fort has the

typical star shape with little corner lookout posts that is common to Spanish

style forts. What is unusual, however,

is that the buildings inside the main wall were built so high they go way above

the top of the wall. You would think

this would have provided the enemies with a great target. Hadn't they heard that it's wise to keep your

head down in a fight.

Elsewhere in Recife is a fort that was also built during

Dutch occupation. This fort has the

typical star shape with little corner lookout posts that is common to Spanish

style forts. What is unusual, however,

is that the buildings inside the main wall were built so high they go way above

the top of the wall. You would think

this would have provided the enemies with a great target. Hadn't they heard that it's wise to keep your

head down in a fight.

Inside the

fort is a small military museum with a few old guns, replicas of all flags

flown over Brazil,

and an exposition of old maps. These

maps were of Recife and Olinda made during the Dutch years. It shows the location of the many forts built

to guard the narrow bay entrance, the layout of the streets, front views of

some of the buildings, and the paths of the channels and shapes of the islands

before any filling and restructuring was done.

Those maps were some of the most fascinating we'd found in

Recife so far. It's always fun to see how things looked so

long ago.

One more

church. We were beginning to get our

fill of churches as we'd seen so many since we arrived in Brazil. This one was nicknamed the "golden

chapel" and you can well guess why.

Inside virtually all the walls and ceilings were covered in gold leaf. Only the places where paintings were held was

there no gold leaf. It's amazing to see,

but rather overdone. It seems you'd go

into this church and be so busy looking at the decoration you'd forget to pray.

That was

enough of Recife. We went back to our hotel and expensive pool

for a good cooling soak and an early night in preparation for our very early

morning flight.

January 20 - 25 Belem

Belem is the Portuguese name for the city of

Bethlehem. It is believed that the town's founder named

it Belem

because he began his journey of exploration up the Guama river on Christmas

day. The town was founded in 1616 when

the Portuguese landed and built a fort to deter French, English, Spanish, and

Dutch from staking a claim. In a

practical move, the Portuguese set up the region of Para and Maranhao, the

northeast of Brazil, under

separate administration from the rest of Portugal. This was because the prevailing winds and

currents made the trip from Belem to

Salvador far longer than the trip from Belem

to Lisbon.

During the

1600s and 1700s the economy of Belem

was depended on the labor of enslaved Indians who knew how to find and extract

cacao, vanilla, cinnamon, animal skins, and turtle shells. As the Indio

slaves died from disease and torture, Portuguese slaving expeditions explored

deeper and deeper into the jungles in search of more. Some Indios did survive by escaping deep into

the jungle up some of the smallest Amazon tributaries. Some of these tribes exist there even today,

living much as they have for eons.

During the

1820s and 1830s there was a period of intense civil was between the white

ruling class and the Indios, mestisos, and blacks known as the Cabanagem

Rebellion. In 1835 the mob descended on

the city of Belem,

expropriated the wealth, distributed the food, and declared independence. Unfortunately for them the British, who were

big beneficiaries of the local trade, put into place a naval blockade which

held these rebels at bay until the Brazilian government could strike back. Unfortunately the Brazilian government took things

a bit too far and even 4 years later they were hunting down and killing anyone

who looked like they might have had a role in the uprising.

In the early

1900s Belem

prospered once again during the rubber boom.

Some monuments to this temporary success were built, the Teatro da Paz

and the docks for instance. But even

this short boom was not to last. With

the decline of the rubber boom, the city fell into a general state of

stagnation. Today the city is humming

along once again at a reasonable pace.

There's quite a bit of restoration work under way and the port is still

busy. It seems fairly prosperous but

probably nothing like it was back in the Rubber boom heyday.

We'd begun

our trip to Belem

at the wee hour of 4AM so we could catch a 6AM flight. Two stops, 4 1/2 hours, one box of cookies,

one sandwich, and a bag of peanuts later we touched down in Belem, in the heart of the Amazonian

jungle. Belem

isn't exactly located on the Amazon river, but

it's close enough. A town of 1 1/2

million, it's almost hard to believe this is a city hacked out of dense jungle.

Once again we

had hotel problems. This time it wasn't

a matter of them being full. It was just

that our first two choices were undergoing complete renovation and were closed,

both of them. We finally wound up in the

little French run Le Massilia pousada that proved to be one of those real

finds. It has just 16 rooms overlooking

a small tropical garden with a little swimming pool. The rooms are all spotless, modern, and

everything works just as advertised. The

French owner speaks French, Portuguese, Spanish, English and a little

German. He has such a welcoming

countenance that it's hard not to feel at home.

You just need to learn to say "Bonjour" and "Comment ca

va?" in the morning.

Friday

afternoon and Saturday morning we did almost nothing other than get to know the

town. The atmosphere of

Belem

is far more similar to the Andes countries

than any other Brazilian city we'd seen so far.

One trip report we'd read indicated that these people thought

Belem was a real

dump. Well, that report had to be taken

in perspective. It was written by a

fellow who flew first class to Rio, who stayed with a former exchange student

who warned them about how bad Belem

was, who stayed in the most expensive hotel in town, the Hilton, and who wound

up having money stolen from his room. So

his view was a little biased.

Belem does have more of the chaotic atmosphere

of the poorer Andes countries as well as a

more down in the heel appearance. It's

not the kind of town you can wander around willy-nilly. You do have to be on your guard. As in La

Paz the sidewalks are crowded with makeshift stalls

where people sell just about anything.

There's clothes, food, electronics equipment, knock-off CDs and DVDs,

cheap jewelry, phone cards, all sorts of stuff.

The only problem is there's hardly enough room to walk. Pedestrians almost need to walk in the

streets if you actually want to get anywhere.

What to do in

Belem? We had a lot of time scheduled for this city. We'd planned it that way on purpose just to

make sure we could get on a boat headed up river and get to Santerem in time to

meet our next flight. But, with so many

northern Brazilian cities it's hard to find much to do after the first couple

of days. We did not have to hurry to do

anything.

We started at

the Goeldi museum/park. Unfortunately

most of the museum itself was closed.

Only a couple of rooms, one containing a few pottery shards and the

other a single pot and a basket, were open to visitors. Surrounding the museum is a small zoo that

has several of the Amazonian animals, birds, fish, and reptiles with signs in

very good English. There were turtles,

turtles, and more turtles everywhere.

Evidently breeding Amazonian river turtles must be quite easy. Also, little capybara run wild all over the

place. They look almost like a tailless,

hunchbacked rat with extra long legs running around on its tiptoes. As a nice, shady park, it makes a pretty good

place to spend another hot, muggy afternoon.

On Monday the

museums, galleries, fort, zoo, and all tourist spots are closed. So the tourist just spends time wandering the

streets looking for every possible air-conditioned nook and cranny in which to

hide from the sweltering heat. Again and

again we found ourselves returning to the Iguatemi shopping and the Estacao das

Docas for relief. The cold, dry climate

of Bakersfield

is beginning to look more and more attractive by the day.

Tuesday, it

turns out, all the museums are free.

Closed Monday, free Tuesday. I

guess that's a good trade-off. We took

this opportunity to visit some that we probably would not have seen

otherwise. The Museu do Arte Belem

housed in a government building built at the height of the rubber baron era was

worth visiting just to see the opulent structure. The fort has a number of relics from the

nearby Ilha Mahjory housed in a, thank goodness, air conditioned room, along

with the reconstructed fort walls, a display on the evolution of the fort

structure, and several canon from the 17th century up to the 19th. Finally the "casa das onze janelas"

(house of 11 windows) houses a modern art exhibit that in no way we would have

paid to see. As we looked at these

modern art contraptions we were constantly wondering who in the world would pay

for these things and being ever thankful that we did not pay to enter this

gallery.

Finally, we did wander back and forth

through the "ver o peso" (see the weight), market several times. It was so named because it was here that the

port authorities originally weighed the incoming imports in order to assess

taxes. The current market building is an

iron structure built in Europe and then shipped in pieces to

Belem for assembly. It's painted light blue and is absolutely

covered with steel rivets. With its four

corner towers, it looks a little like a light blue castle. Inside the smell of fresh fish pervades as

this building now houses the main fish market.

Each morning the fishermen in their bright white wooden fishing boats

unload their catch, clean in, weigh it, and display it for sale. We saw some mighty big fish sitting on the

tables in there.

Finally, we did wander back and forth

through the "ver o peso" (see the weight), market several times. It was so named because it was here that the

port authorities originally weighed the incoming imports in order to assess

taxes. The current market building is an

iron structure built in Europe and then shipped in pieces to

Belem for assembly. It's painted light blue and is absolutely

covered with steel rivets. With its four

corner towers, it looks a little like a light blue castle. Inside the smell of fresh fish pervades as

this building now houses the main fish market.

Each morning the fishermen in their bright white wooden fishing boats

unload their catch, clean in, weigh it, and display it for sale. We saw some mighty big fish sitting on the

tables in there.

At the wee

hour of 4 AM the phone rang and the alarm went off. Time to head out on the one organized tour

we'd decided to subject ourselves to.

Usually if we can visit a site on our own we do. Tours are just too organized and

limited. In this case, however, we

wanted to visit an island for which there was no public transportation. Just 1/2-hour boat ride toward the ocean is a

small island with an unusual feature.

For some reason parrots have decided to make that particular island

their nighttime roost. At this time of

year over a thousand Amazon Amazonica parrots rest on that island every

night. At other times of year other

migrating parrots join the party making up a flock of some 6 to 7000

birds. Every morning at sunrise the

birds wake up, squeak and squawk, then fly off in pairs to their daytime

feeding grounds.

We stood in

the quiet of the early morning, rocking gently on the boat. We'd joined a couple of English travelers and

a huge group from French Guiana. We stood quiet in the bow while some wise-guy

French speaking fellow at the stern kept cracking jokes. It would have been far more pleasant enjoying

the tranquility of this river scene. At

just a little after 6Am a sudden squawk hit the air. That was just the start. For the next hour the loud din of these very

vocal birds filled the air and flocks upon flocks headed for the sky.

In the early

morning light it was almost impossible to tell the birds were different from

any other we've seen. Yet as daylight

grew we could finally start to make out the green flash of wing feathers and a

little yellow around the eyes. Although

even well into sunrise we still could not tell what kind of birds these were.

These Amazon

Amazonica parrots are the only ones that live in the coastal mangrove forests

of Brazil. They're about 1 1/2 ft in length and have

very short, stubby wings. These are not

birds made for soaring. Rather they have

a very short and fast wing beat needed to keep them aloft. And they do like to squawk while flying. Seems to be some sort of messaging between

the pairs as sometimes they even squeak in unison.

There wasn't

anything else to the tour. Just a ride

in a boat down to the island, an hour or so at anchor while we watched the

birds, and a slow boat ride back. It was

rather expensive for what you got, around $30 each. But there's no other way to get there and

where else do you have the opportunity to watch over 1000 parrots. Although we had thought we'd get a much

closer view than we did so in that respect is was a bit of a disappointment.

January 25 - 28 The Amazon

There are

many ways you can explore the Amazon.

There are package trips that include guide, scheduled tours, first class

boats, and all the works. On these tours

you do the same old stuff; take a walk in the forest, see medicinal plants,

visit a local family, try your hand at a blowgun and piranha fishing. We'd already done all this and had no

interest in doing it again. So that

option was out.

There are

also huge cruise ships that sail up river.

These gigantic hotels on water must look entirely out of place against a

backdrop of rustic wooden houses lifted up on poles and small canoes or packet

boats. In addition, with the passengers

so high above the locals how can you ever interact.

You could try hiring your own boat crew, a difficult,

uncomfortable, and probably expensive.

Or you could

do what the locals have done for decades, buy a spot on one of the transport

boats. There are about 4 that run

upstream each week taking 2 1/2 days to get to the midpoint

port of Santarem

and 5 days to get to Manaus. On Wednesday, the day we wanted to go, it

happened that the largest passenger boat was departing. It was also one of the newer boats, newer

being a relative sense here. So we

thought it'd be the most comfortable and most interactive way to get up stream. Although there was no way we were going to go

all the way to Manaus. Santarem

was more than enough.

Our boat, the

NM Amazon Star, carried a total of 850 passengers. The majority of these passengers are housed

in one of 2 hammock sections. The lowest

class hammock section, lowest in cost and location, houses about 300

people. They're on the lowest deck that

has open sides and no air conditioning.

They string their hammocks up so they are literally shoulder to shoulder

four in a row. Baggage is strung out on

the floor below. They share toilets, 4

or 5 for men and women, and they eat in a stuffy, hot unair-conditioned room

way at the back where all the engine fumes congregate. Showers during the trip are obtained from

using the on deck open showerheads that are turned on for 3 hours in the morning

and 2 in the evening. Not an especially

great option.

Second class

hammocks have very nearly similar arrangements with the exception that glass

windows enclose their deck and supposedly they have a/c. Although it seemed that the a/c often wasn't

working properly. These folks do get to

eat their meals in the a/c restaurant, although the meals aren't all that

great. We accidentally ate their

breakfast one morning as we were having trouble interpreting when we should

eat. They got one tasteless roll, one

piece of fruit, and coffee. We returned

later at our proper seating time to find that the cabins get all the fruit and

rolls you can eat as well as cold water, juice, ham, cheese, and crackers. Quite an upscale.

The next step

up are the camarotes. There are about 44

of these although some house crew members.

These folks have a small room with 2 bunk beds and an individual

a/c. They share a set of 2 toilets per

deck and 2 showers. The cabins could be

quite comfortable for 1 or 2 persons.

But it seems that folks are allowed to pack in children plus tons of

luggage which must make it extremely tight.

Finally there

are the suites. These are almost

identical to the camarotes with the exception of a small bathroom with a small

shower as well. These are not luxurious

cabins, there's a lot of rust on the metal, mattresses are thin, and bedding

consists of a lower sheet and pillow only.

But the room does have enough space for to add 2 plastic chairs and the

bathroom was nice to have. We got the

full upscale meals as well. The suites cost

around twice the cost of the second class hammock section, but we concluded

they were well worth it. We were far

more comfortable than most other travelers were.

By taking the local transportation we had

the opportunity to really see what river life is like. The first thing that surprised us was the

fact that the boat didn't seem to stop very often. We had expected a stop after the first day at

the town of Breves. But that just didn't happen.

By taking the local transportation we had

the opportunity to really see what river life is like. The first thing that surprised us was the

fact that the boat didn't seem to stop very often. We had expected a stop after the first day at

the town of Breves. But that just didn't happen.

Along the

route there aren't that many towns and the ones we saw were extremely

small. Mostly there are small wooden

houses all standing on stilts. The house

is small, but it usually has an accompanying roof covered shelter where much of

the daily work is carried out. There are

pole-mounted docks everywhere. In places

where more than one house has been built there will be pole-mounted walkways

connecting them together. Every house

has at least one wooden canoe and often these square looking packet boats that

are the equivalent of the local bus.

On the river we saw some barges floating

lumber or tractor-trailers up or down stream, a few of the packet boats, and

lots and lots of wooden canoes. The

folks in the canoes were the most amazing.

First, the age of some of the youngest canoers was incredible. Kids that looked to be no more than 3 were

out on the river in their own canoe, no adults, no life jackets. These kids must learn to swim and paddle a

canoe before they even walk.

On the river we saw some barges floating

lumber or tractor-trailers up or down stream, a few of the packet boats, and

lots and lots of wooden canoes. The

folks in the canoes were the most amazing.

First, the age of some of the youngest canoers was incredible. Kids that looked to be no more than 3 were

out on the river in their own canoe, no adults, no life jackets. These kids must learn to swim and paddle a

canoe before they even walk.

There is a

tradition whereby folks on the passenger boats will pack up food, clothing or

other store bought items into plastic bags.

These are tossed to the waiting canoes.

One man told us they do this in part because there are no stores

anywhere nearby. There are a few small

"portos" where the locals can buy such as beer and gasoline and there

are a few floating stores that go from house to house. But otherwise they are living mostly on what

they can find in the forest. The plastic

bag wrapped gifts are meant as some assistance.

Almost every house we passed had a canoe out on the water filled with

either one person or the entire family.

So many had hopeful looks on their faces. They were cheerful and waved

as we went by. But, you could sure see a

little look of disappointment on some of those faces when not a bag hit water

near them. In this case it was much

better to live further downstream where the pickings are greatest.

The most

incredible act of the canoers was the hitchhiking. That's right.

As our boat would approach we'd see a canoe coming in perpendicular at

full speed. Usually there were 2 people

on board, women and even kids were included.

As the canoe neared, the bow person would take up a grappling hook while

the stern person continued to paddle and steer.

When close enough the person in front with the grapple would reach

forward and hook something on our boat, usually a tire or another canoe. Often the sudden shock of the canoe being

turned 90 degrees and accelerated up to our boat's speed would pull the bow up

and swamp the rear. The aft person would

use their paddle as a rudder while the fore person would hastily tie off the

grapple hook, climb aboard our boat, and attempt to secure a second rope while

pulling the bow of the canoe up onto one of the tires. The helmsman would then use the paddle to get

some of the water out of the canoe. It

all looked highly dangerous to us.

We saw one

instance where one very, very strong fellow paddled like crazy and still missed

the grapple. So he grabbed his bowline

and jumped into the nearest dragging canoe letting his own canoe drag behind on

the line. Now that was daring. We're convinced he did it just to show off as

he seemed to be moving too slowly at the start of his run. It was as if he gauging his distance to make

this show. It was quite a feat. We never saw him in the upper parts of the

boat and we wondered if those in the lower, hammock section were handing out

tips.

Once aboard,

the canoers would sometimes come around ship selling goods such as palm hearts

in a jar, shrimp, acai fruits, and sugar cane.

These entrepreneurs were making a killing and often would leave ship

with empty canoes and full pockets. Or

they would just hook on for the upstream ride.

Often they carried large plastic fuel containers to be filled at the

local porto. For one thing we did notice

is that these isolated little houses all have a generator, a few electric

lights, a TV, and a satellite dish.

They'd float down river to the porto for the few goods carried there and

then hitch a ride back up.

Our canoe

hitchhikers came and went all day long.

One hour you'd look down to see one set.

An hour later there'd be an entirely new crop. There were so many canoes attached to the

sides and stern on our boat that one passenger said he counted 21 at one

time. Now this was a part of river

travel no cruise liner would ever see.

In fact, we were told that most riverboat captains will not allow the

hitchhikers. So we were lucky. It was the best part of the whole adventure.

Getting the canoes disconnected was an

even trickier maneuver. If there were

another canoe in the way it would be difficult to get yours out without getting

tangled. Often the inexperienced boys

would get swamped. We watched one trio

while their canoe went under the one behind and one by one the boys got left

behind in the river. With some effort

from someone aboard out boat, the canoe eventually let go. Fortunately these boys are expert swimmers,

there are always other canoes around to help, everything they own floats, and

the current isn't especially strong.

They were fine. But, it seems

that one-day some of these canoers will get hurt or killed and this old

tradition will come to an end.

Getting the canoes disconnected was an

even trickier maneuver. If there were

another canoe in the way it would be difficult to get yours out without getting

tangled. Often the inexperienced boys

would get swamped. We watched one trio

while their canoe went under the one behind and one by one the boys got left

behind in the river. With some effort

from someone aboard out boat, the canoe eventually let go. Fortunately these boys are expert swimmers,

there are always other canoes around to help, everything they own floats, and

the current isn't especially strong.

They were fine. But, it seems

that one-day some of these canoers will get hurt or killed and this old

tradition will come to an end.

Today going

up the Amazon on the passenger boat has to be about the closest thing to riding

up the Mississippi

in the days of the paddle wheelers as you can get. Yes the propulsion system is different; you

don't have to stop to load on wood all the time. But the river life has to be very similar. Mark Twain notes in his book "Life on

the Mississippi"

how there were just scattered houses along the way, usually on stilts. Everyone went everywhere in boats, rowboats

or rafts. Everything, absolutely

everything, revolves around the river, as there are no roads.

Life aboard

the boat quickly becomes a repetition of the same thing day after day. We'd chosen to take the boat only as far as

Santerem figuring that 2 1/2 days was plenty.

We'd heard many times that while staying on for the full 5 days is quite

an experience, it is also a huge relief to get off. We figured that 2 days would be more than

enough to get a feel for river life.

You're not going to see animals, so it's things like these daring

canoers that you come to see. So while

we settled into our 2-day adventure housed in our little suite under the care

of the ever-watchful cabin guardian, Vitoria,

we lazed the days away. And yes we were

quite ready to get off the boat by the time it reached Santarem.

January 29 - 31 - Santarem

Santarem is a small town of around 200,000

located almost exactly midway between Belem and

Manaus on the mighty Amazon river. It is an isolated city carved out of the

middle of the dense jungle with primary access only through the river. It's a place that gets hot and steamy during

the day and just slightly less hot and steamy at night. Even the daily rains do nothing to mitigate

the oppressive heat.

Early

European explorers came to the Santarem

area in the early 16th century. Their

chronicles give accounts of swarms of canoes coming out to do battle and Indian

long houses lined up along the riverbanks.

In fact archeological evidence indicates that people had been living in

this region for over 10,000 years. It

wasn't until disease and slavery decimated the locals that the Amazon attained

its current unpopulated appearance.

Santarem began life as a Jesuit mission in the

17th century. It grew slowly

experiencing short booms during the rubber era and just after the construction

of the road to Cuiaba. One of its most colorful events in

Santarem's history

involved henry Ford. In an attempt to

kill the British monopoly on rubber, Ford set up a similar rubber tree

plantation program that the British had going in Asia. Unfortunately for Ford the site selected was

not suitable for growing rubber trees.

He never did manage to get the rubber program off the ground, but he did

leave an interesting legacy. There are

two nearby towns; one that is called Fordlandia and to this day mimics a

Midwestern town.

In Santarem

there's little to see or do. There's one

small but surprisingly good museum and a church or two. Outside of town is the small beach community

of Alter do Chao where most Saltaremos go to shake off some of the heat on

weekends. Alter do Chao is popular only

because it has a long white sandy beach and clear water. There are many things, some very large and

very vicious, lurking in the muddy waters of the Amazon and many even who were

born and raised on its banks are afraid to enter.

In Santarem

there's little to see or do. There's one

small but surprisingly good museum and a church or two. Outside of town is the small beach community

of Alter do Chao where most Saltaremos go to shake off some of the heat on

weekends. Alter do Chao is popular only

because it has a long white sandy beach and clear water. There are many things, some very large and

very vicious, lurking in the muddy waters of the Amazon and many even who were

born and raised on its banks are afraid to enter.

We went over

to Altar do Chao for an afternoon just to see what was there. As expected we found a beach covered with

beach chairs, umbrellas, and swimsuit clad bodies. There were swimmers in the water and canoes,

kayaks, motor boats, water skiers, and tube riders on top. The primary beach is located across a lagoon

on a white sandy spit of land. In low

water season you can wade across. At

this time there was a brisk business of rowboats porting people back and forth

all day long. There's a continual stream

of boats crossing and recrossing which was a rather amusing sight to see.

We hadn't

come to swim, just to watch and walk along the beach. UV ratings this close to the equator and at

the middle of the day reach the 10 mark.

Even just sitting in the shade on our Amazon boat we were still getting

burned over and over again. So we covered

up, endured the heat, and just sat in the shade to watch the swimmers and

boaters. The sun is just too brutal for

us northerners.

Despite not

having much to visit in the way of museums, the little city of

Santarem proved to be quite interesting. All along the new, concrete river walk the

river life that is the mainstay of this city buzzes with activity day and

night. For over a km there are

riverboats of all sizes tied up, pulling in, or departing, loading, unloading,

or just waiting for their next departure.

With the water at midlevel, people had to climb down about 10-foot

ladders to gain access to the boats.

However, we heard that at high water it's even possible for the river to

overrun the wall and flood the city.

Amazon river boats come in all sorts of sizes but are

usually of a common style. Their hulls

are long and narrow with fairly rounded bows and sterns. They have flat decks and roof and can be from

one to 3 decks high. They're made of

wood, painted white with colorful, usually blue, trim. The lower deck is usually used for cargo and

the upper for passengers. Wooden

railings surround all decks. At the

front and back of the upper deck there is usually small cabin space for the

bathroom, crew cabins, passenger cabins, galley, and the wheelhouse. When in transit, the space between cabins

becomes absolutely filled with hammocks.

Amazon river boats come in all sorts of sizes but are

usually of a common style. Their hulls

are long and narrow with fairly rounded bows and sterns. They have flat decks and roof and can be from

one to 3 decks high. They're made of

wood, painted white with colorful, usually blue, trim. The lower deck is usually used for cargo and

the upper for passengers. Wooden

railings surround all decks. At the

front and back of the upper deck there is usually small cabin space for the

bathroom, crew cabins, passenger cabins, galley, and the wheelhouse. When in transit, the space between cabins

becomes absolutely filled with hammocks.

Given the

shape and characteristics of these river boats, you'd just need to add a couple

of black smoke stacks and a big wheel on the back or sides and you'd have

precisely the kind of paddle wheel boat that used the ply the waters of the

Mississippi. With over 50 boats tied up at the river front

railing to railing at all times, all the activity including animal traffic, and

the shape of the boats we could easily imagine what a typical Mississippi river

city of, say of the was like. We felt as

though we were getting a rare peek into the past.

There are

probably very few places remaining where you can get this kind of unique

view. We did not see it in

Belem because our up

river transport did not depart from the main docks. Even at Manaus

it didn't quite feel the same. The boats

there are larger, more uniform in size, the docks more structured, and the

access more difficult. So while in

Santarem we just couldn't

resist watching this boat activity all day long. We spent hours and hours walking up and down

the river walk or finding shady places to sit and watch this remarkable scene.

We weren't

the only ones. The new and improved

river walk is a continuing project of the Santarem

municipality. Recent additions were put

in place in 2000 and the materials for more distance currently sit on shore

waiting funding to be put into place. At

the time we visited there was over 3 km of walkway available and every evening

the townfolk come out to stroll or jog its length. But, nothing compares with Sunday.

On Sunday

evening, as the sun sets and the river walk finally moves into the shade, it

seems that the entire town comes out from their houses and descends on the

walkway. While just one block inland the

town is dead quiet, the riverfront is absolutely alive. Families bring their kids to the park to play

on the swings. Teen-age girls come out

in their finest version of the latest styles to get noticed by the teen

boys. The elderly bring folding chairs

to sit by the wall and people watch.

Vendors selling fresh cooked pizzas, hotdogs, hamburgers, and hot

sandwiches pull their carts alongside the wall and set out cushions for

seating. Balloon vendors, candy sellers,

and even a fellow who converts old cans into unique caps all come to the park

to sell their wares. This is the place

where all the activity can be found.

Even though

we arrived at Santarem

wondering whether we should have made our stay a day shorter, we wound up

finding it a great place to make a stop.

In the end it will probably prove to be one of the most memorable places

of our Brazilian trip. The entire scene

was so amazing. We wouldn't have missed

it for the world.

February 1 - 3 Manaus

Manaus is located about 1000 miles up the

Amazon which really is less than 1/2 the total distance of the river. It's a huge city of 1.7 million whose only

access is either by a road-stretching north to Caracas or by ship. Virtually everything you

find in the stores has to be brought in by boat and, consequently, prices are

significantly higher. To encourage

investment and development in the region, Brazil set up part of the city as a

duty free zone. The idea was to

encourage development of manufacturing plants and bring money into the

region. What it wound up doing was

bringing a lot of people into an area way in the middle of nowhere and a lot of

import companies. It helped a few people

right in the area, but did little for the rest of Brazil.

Tourists usually

come to Manaus

to make some sort of excursion into the jungle.

Usually this is in the form of a Jungle lodge visit. However, coming to Manaus to see wildlife at one of the local

lodges is just wishful thinking. With a

city of this size, almost all wildlife within a 250-km radius has been woefully

reduced in numbers. You'd have to

venture way up one of the small tributaries to regions where only the local

Indios have the skills to penetrate.

Then you'd have to stay in this backcountry for weeks or even

months. Maybe then, if you are real

lucky, you might see some wildlife. But

don't count on it. It's easy to imagine

all those wildlife shows put on by National Geographic. But, you have to realize that those

photographers and movie producers do exactly what we just described.

If you do opt

for a jungle lodge visit you'll see lots of plants, probably those 1 inch long

poisonous ants, lots of insects, maybe frogs, some birds, and probably a few

caged animals. All the lodges do the

usual piranha fishing, which may yield a few nibbles and not much else, a visit

to a local family, a blow gun contest, walks in the forest, and some discussion

of the medicinal uses for the various plants.

Not much else.

Having done

all these things at the Yarina lodge in Ecuador the year before we opted

not to do it again. That did not prevent

the multiple of tour guide operators from trying to get us to sign up. At the airport, walking down the street while

looking for a laundromat or in front of the Teatro Amazonas obvious jungle tour

salesmen continually approached us. We

quickly got to the point of ignoring their usual introduction query of

"Are you looking for information?"

Manaus downtown is not a particularly

attractive city. Very few of the

buildings from the rubber boom days remain and most that do are in wretched

condition. During the day the sidewalks

are crammed with pedestrians and street vendors. It is almost impossible to walk anywhere at

any faster pace than what the throng is moving.

Brian would manage to squeeze past a row of pedestrians just as they'd

close ranks and I'd be stuck strolling along behind. At night, after the venders shut down, you

find a street filled with trash both from the stores lining the streets and

from the pedestrians. Brazilians have

that very common Latin American litter habit.

Choosing not

to head out on another jungle trek, we spent our time trying to find things to

do in the town. There were a few

museums, Museu do Indio

and Museu Amazonica both house essentially the same types of displays. They both have feathered headdresses,

pottery, baskets, blowguns, arrows and bows.

Explanations for the items were in Portuguese, if they existed at all,

but the Museu Amazonica did provide a good English-speaking guide.

Such a nice

lady, she added so much to the exhibits that we would not have gotten

otherwise. She told us about the ritual

the young girls of one nearby tribe go through after their first menses. Their hair is pulled out, they are restricted

to their homes for 6 months, and they're only allowed to see their mother or

sisters during the entire time. After

the 6 months they come out looking somewhat white, white compared to the

natives but still dark compared to us northern Europeans. Immediately she is married and expected to

produce children. Our guide told us

she's encountered 10 year old Indios who were already pregnant. One grows up fast in those societies.

The boys get to go through their own

particular form of puberty rites of passage.

They are required to stick their hand into a woven basket that is full

of those poisonous ants. They get stung

many times and have to endure a full day of wrenching pain and sickness. Any boy who refuses to pass this test is not

considered a man. What fun.

The boys get to go through their own

particular form of puberty rites of passage.

They are required to stick their hand into a woven basket that is full

of those poisonous ants. They get stung

many times and have to endure a full day of wrenching pain and sickness. Any boy who refuses to pass this test is not

considered a man. What fun.

After visiting

the museums we made an impromptu stop at the Palacio Rio Negro. Behind this lovely old rubber baron's mansion

we found several full size examples of typical Amazonian structures complete

with English explanations. There was a

river dweller's house, a typical riverboat, a tribal roundhouse, a rubber

collector's workshop, a shop for converting the manioc root into powder, and

several other buildings. This was

perhaps one of the most interesting museums we've seen in Brazil. It's almost, but not quite, like a living

history museum. Definitely well worth

the stop.

Of course we

had to visit the Teatro Amazonica. This

incredibly opulent building was first envisioned in 1881 and finally

inaugurated in 1896 following several years of no work due to massive

corruption. It operated for 72 years and

then was shuttered after the collapse of the rubber boom. It was not restored and reopened until 1997.

It's a

beautiful structure; very similar in form to the Teatro do Paz in

Belem only seemingly a

little bit more sophisticated. Except

for the odd dome on top. The then

governor purchased this colorful tiled dome while on a trip to Europe. He saw the

dome and decided, on a whim, it would be nice to add to the theater. It looks wholly out of place especially since

it was never envisioned in the original design.

Imagine the architect's horror when, upon his return, the mayor proudly

presents this huge colorful dome to be perched atop this elegant theater

structure.

The theater is constructed mostly from articles

imported from Europe. Italian marble, French chandeliers, iron

columns from Scotland, and

even an electric generator from the US.

Even though the wood is of local origin, much of it was sent off to Europe for carving.

So it really was a European theater stuck out in the middle of the

Amazon jungle.

The theater is constructed mostly from articles

imported from Europe. Italian marble, French chandeliers, iron

columns from Scotland, and

even an electric generator from the US.

Even though the wood is of local origin, much of it was sent off to Europe for carving.

So it really was a European theater stuck out in the middle of the

Amazon jungle.

The building

was designed with a few rather interesting technical innovations. Under the main floor there are air

passages. Every 2 or 3 rows there are

large round disks under the seats. These

are ventilation shafts used to admit some cooler air during the show. They're still in place only for show as the

entire theater today has air conditioning.

The interior

columns are all made from Scottish steel.

The idea was that the steel would better reflect the sound than wood or

plaster thus improving the acoustics.

Also, outside the entire drive that used to encircle the theater was

originally paved in a composite of rubber and stone. This was intended to deaden the noise of late

arriving carriages. The doors to the

theater were left open during performances so any external noise would be

distracting. Finally the electric

generator was used to light all the chandeliers as well as the interesting

lampposts out on the street. This was

probably one of the few buildings in all of Manaus that had electric lighting so it must

have been quite a sight at show time.

We did have

the unique opportunity to experience a performance in the theater. It happened that on our last night there was

a free concert put on by the Manaus

orchestra. It was an hour or so long

show with a small string ensemble. Most

of the music was good, although their final piece was rather weird. Best of all was the fact that it was free one

of the few free things we've found in Manaus.

The last

thing we visited was the local zoo run by the army. This branch of the army is different in that

they are not trained to fight other armies.

They're supposed to be in charge of protecting preserved sections of the

Amazon. How good a job they're actually

doing remains to be seen. Our guide in

the Museu Amazonica told us that even though the citizens of Manaus keep

replanting the Pau Brazil trees, 20 or 30 years later companies keep coming

along and chopping all their trees down.

So maybe the army isn't all that successful after all.

Anyway, this

zoo houses examples of Amazonian fauna that were "rescued" by the

army. Or, as one Dutch fellow we met

proposed, maybe they used these animals to study and for training. In any event, it's here in this zoo where

you'll see the most Amazonian animals.

Certainly far more than you'll see in any jungle lodge. There were all kinds of parrots, two harpy

eagles, a toucan, some tapirs, several of the larger cats, turtles, crocodiles,

and an interesting small cat they called an Eyra cat. Looking at our Amazonian animal reference

book we concluded that it is actually a jaguarundi. It's not much larger than a house cat with a

longer, sleeker body and a dark silvery gray coat. The sign claimed that these cats could be

found from Texas

to the Amazon. We'll have to check on

this, as

we've never heard of them being in

Texas.

we've never heard of them being in

Texas.

The Brazilian

phone company has a lot of fun with its public phone booths. There are the normal ones, the funny blue

fiberglass covers that have been given the nickname "ear". Then there are the more unique. We've seen phone booths made to look like

coconuts, ancient pottery, a crab sitting on top a carved coconut shell bowl, a

cashew fruit, fish, piranha, and parrots.

Here in the zoo the company went to extremes. They've got phone booths dressed up like

large cats, tapir, capybara, crocodiles, parrots, and toucans. It's fun to see a new version of the phone

booth and even more amusing to see someone standing talking into the belly of

some gigantic bird.

The zoo was

well worthwhile even though the cages were more reminiscent of early zoos

rather than the more commodious accommodations now built in such places as the

San Diego zoo. At least we did get to see some of the

animals on our list of must see, even if they were captive.

February 4 - 9 Cuiaba

Around 1000

miles back south, a long way from the equator and the Amazonian river basin, we

headed for our final stop on our Brazilian adventure, Cuiaba and the Pantanal.

Cuiaba itself has just a few items of interest

to the tourist. We stopped in at the

municipal aquarium where we had the opportunity to see several of the fish

species that inhabit the river right out in front of the building. The tank full of piranha was most exciting. Such calm, innocent looking fish. There is also a small historical museum that,

unfortunately, was closed for renovation when we arrived. So we found ourselves just wandering for a

full day while we waited for the day for which we'd reserved a car. Once we had that car, however, we were off

and running.

While the

Amazon is the place to go to experience the river life, the Pantanal is the

place to go to see wildlife and Cuiaba

is one of the main portals to the Pantanal.

Around 500 million years ago this are was covered in ice. Another 200 million years later it was

covered by a shallow sea. Eventually the

Andes rose up while the area of the Pantanal

remained low or even sank. Today it is

still somewhat a shallow sea that is drying up.

More like a seasonal swamp, as it is usually flooded for 6 months and

dry for the other six.

What makes it

so easy to see the wild life is that it has mostly grass lands with islands of

tree covered high ground. When flooded,

the grass lands become swamps and the wild animals congregate on the high

ground. In the dry season the wildlife

congregates around the few ponds. So

visiting either time of the year will usually yield good wildlife viewing. Yet again, there is always the element of

luck involved.

The lands that are really known as the

Pantanal start just 10 miles south of a little town called Pocone which is

around 75 or so km south southwest from Cuiaba. There is a dirt road that continues around

150 km further south deep into the Pantanal itself. Originally intended to provide a direct

connecting road between Campo Grande and

Cuiaba, the government

eventually gave up on the idea figuring that it would be unwise to build a road

through a region that is flooded half the year.

Today this rough dirt road can be traveled using even the small VW Gol

car for as far as you feel comfortable.

The lands that are really known as the

Pantanal start just 10 miles south of a little town called Pocone which is

around 75 or so km south southwest from Cuiaba. There is a dirt road that continues around

150 km further south deep into the Pantanal itself. Originally intended to provide a direct

connecting road between Campo Grande and

Cuiaba, the government

eventually gave up on the idea figuring that it would be unwise to build a road

through a region that is flooded half the year.

Today this rough dirt road can be traveled using even the small VW Gol

car for as far as you feel comfortable.

Along the

Transpanteira there are over 100 wooden bridges that are periodically

rebuilt. The further from Pocone you get

the less often the bridges are rebuilt.

We went as far as around 117 km, actually passing the 4 or 5 men who

were tasked with bridge reconstruction, and finally came to a bridge that

looked just a little too rickety. Here

we turned back and returned to Cuiaba.

As our luck would have it, we were not

fortunate enough to see as many of the mammal species as we'd hoped. One deer and an armadillo was it. We did add a large number of other animals to

our "have seen" list including: roadrunner lizards, several iguanas

including one bright green one, a large whip snake, and some crocodiles. Yet it was birds we spotted the most, an

amazing variety of birds. We saw loads

of snowy egrets, gray storks, hawks, vultures, kingfishers, and parrots. In addition we were fortunate enough to spot

no less than 4 toucans including the toco toucan with its black body and orange

beak, 4 huge white storks with their red neck ring and black neck and head, one

mottled brown burrowing owl, and one large eagle with a brown back and creamy

white head. Plus all sorts of little

birds with colors ranging from bright orange to pure black.

As our luck would have it, we were not

fortunate enough to see as many of the mammal species as we'd hoped. One deer and an armadillo was it. We did add a large number of other animals to

our "have seen" list including: roadrunner lizards, several iguanas

including one bright green one, a large whip snake, and some crocodiles. Yet it was birds we spotted the most, an

amazing variety of birds. We saw loads

of snowy egrets, gray storks, hawks, vultures, kingfishers, and parrots. In addition we were fortunate enough to spot

no less than 4 toucans including the toco toucan with its black body and orange

beak, 4 huge white storks with their red neck ring and black neck and head, one

mottled brown burrowing owl, and one large eagle with a brown back and creamy

white head. Plus all sorts of little

birds with colors ranging from bright orange to pure black.

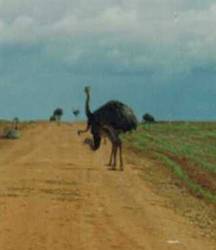

Even after we

left the lowlands of the Pantanal to hit the higher grounds of the Chapada das

Guimereos, we saw even more parrots and a big flock of those gigantic

rheas. The rheas were busy nipping seeds

or insects from some farmer's newly planted fields. Certainly we would have to say we did see far

more wildlife around Cuiaba

than we ever did in the Amazon, even if we did not get to see the mammals we'd

hoped for.

After the

long, slow drive up and down the Transpanteira we headed 5-km northeast of

Cuiaba to the cliffs of

Chapada das Guimereos. When the Andes were rising and the Pantanal was lowering, the

Chapada was also going up, a little.

It's less than 3000 ft above sea level, so it did not raise all that

much. The area that rose makes a sharp

cliff going east to west. Wind and water

erosion over the eons have produced dramatic canyons, caverns, caves, and rock

sculptures. These can be visited in the

Parque Nacional Chapada das Guimereos.

We entered

the park at around 9 AM hoping to get in some descent hiking before the heat

and humidity of the day set in. Lucky

for us we arrived on a day that started with a cool, misty fog. By the time the mist burned off, around 4

hours later, we'd finished hiking the few trails that there are and were ready

to head back to Cuiaba. One thing you quickly learn is that just

minutes in the Brazilian heat and you're covered from head to foot in

sweat. It's just not a comfortable place

for extreme activity.

Chapada das Guimereos park is situated

along the edge of these red eroded cliffs whose total height is only about

1,000 ft. The red rocks in their

bizarrely eroded forms look a bit like the hoodoos of Bryce

Canyon in Utah.

The valleys are covered in dense green jungle, a perfect hideout for

some of the park's residents including monkeys.

The top of the cliffs are covered with short bush size trees and

grass. The upper cliff lands must be

ideal for farming, as there are huge farms all along the top. We're talking thousand acres, fully

mechanized farms. It was on one of these

farms where we saw all those rheas munching on the seeds. The park, at least, has been left natural.

Chapada das Guimereos park is situated

along the edge of these red eroded cliffs whose total height is only about

1,000 ft. The red rocks in their

bizarrely eroded forms look a bit like the hoodoos of Bryce

Canyon in Utah.

The valleys are covered in dense green jungle, a perfect hideout for

some of the park's residents including monkeys.

The top of the cliffs are covered with short bush size trees and

grass. The upper cliff lands must be

ideal for farming, as there are huge farms all along the top. We're talking thousand acres, fully

mechanized farms. It was on one of these

farms where we saw all those rheas munching on the seeds. The park, at least, has been left natural.

There are

about 4 to 5 km of trails within the park.

Probably 95% of Brazilian visitors simply walk the 50 or so meters to

the veu da Noiva (overlook of bridal veil falls). With a vertical drop of 85 meters over a

recessed cliff, this is the most spectacular falls in the entire park. As we find so often in the U.S. people in

the parks will do as little as they possibly can. They drive to the overlook, get out of their

car (maybe), take one look, and leave.

Brazilians are no different. One

family who arrived just as we were leaving walked to the overlook and then

returned to the restaurant to eat. Lucky

for us this meant that we were able to hike the rest of the trails absolutely

by our selves.

The trails

aren't well marked. You're left guessing

where you are until you do happen across one of the few signs that gives you

some indication of where you are. The

trail heads out across the flatlands on the top of one of the eroded

peninsulas. Then it drops over a

precarious route to the edge of the river that it follows for about 1-km. There are side trails to a series of 4

waterfalls each having drops of just a few meters. In some places in the U.S. these

would be considered to be just a series of large rapids. But here, in this relatively flat country,

they're waterfalls. Probably the main

interest for any Brazilian are the pools that form under the falls. One thing we learned about Brazil is that

swimming seems to be the most favorite pastime.

We wandered

around the park for several hours until the heat and humidity became just too

oppressive. We scanned the treetops

hoping to see a monkey or two with no luck.

We did get to see another flock of green parrots, a bird that seems to

be quite common here. After that it was

time to return to Cuiaba

and prepare for our flight back to LA.

So much for Brazil and

South America.

It's time to concentrate on another continent.

References:

Lonely Planet

Brazil,

2005 edition